How to Study for Exam 6, an Architect’s Way

We begin where many works end, with a glossary.

Part 1: Glossary

Site

The site is a place where a certain action will be taken. In architecture, the action is to design and to build. In the realm of a CAS exams, the action is to study and to test. These two actions could not be more remotely disconnected, and yet as a trained architect aiming to take and hopefully pass Exam 6, I found myself sitting in a cafe, faced with the challenge of preparing for the exam in a little less than 6 weeks.

Program

The program is a collection of contents that needs to be contained. In architecture, the container is a building. In the CAS realm, the container is an exam. Building programs range from glamorous hotel lobbies to utilitarian family toilets. For Exam 6, the program is notoriously wide, ranging from insurance regulations to sophisticated tax policies. Architecture programs are documented in a client’s program guidelines. Exam 6's program is specified in a syllabus on the CAS website. However, if, like me, you don’t have fancy study guidebooks, you can reverse engineer a detailed program using past exams, a strategy I will explain later.

Timeline

The timeline is one of the most important items for a project. The architect usually first proposes the timeline, which is continually changing due to factors such as funding, client revisions, and yet more client revisions. The timeline for a CAS exam is also a crucial component of the study process, but with less flexibility because it’s mostly reversed engineered from the date of the exam. And instead of client revisions, there will be a lot of more unexpected extra time needed to learn. One of my construction material professors once wisely said, “everything takes three times as long as you estimated,” a statement that has proven true in every scenario of my career.

Deadline

A deadline is the date when everything comes together. In architecture school, it’s the same as “pen down” date: a specific date and time where you stop doing whatever you were doing and put your pen down and deliver what’s asked of you. In the CAS exam realm, the deadline is the date of the exam day, a day when you stop absorbing information and release whatever information you have absorbed.

Scope

A scope draws a line between the needed and unneeded. In architecture, the scope is declared in the client-architect contract.

The type of project: a building, an urban plan, or a masterplan.

The level of completion: feasibility study? Conceptual proposal? Schematic Design?

The scope helps the architect identify the timeline and allocate the resources to a project. The site and program are also defined in the scope.

In the CAS realm, the scope is to study for all the programs defined in the site within the current timeline, so that I/you can pass the exam within the deadline.

Part 2: Strategy

Prioritize. Don’t spend all your time on the toilets and elevators.

In a world of limited resources, to strategize is as important as to execute. The key to passing an exam is not to study and master all the contents of the exam, but to learn and grasp certain things well enough to hit the passing score. Everything else is extra, and with limited time, not worthwhile.

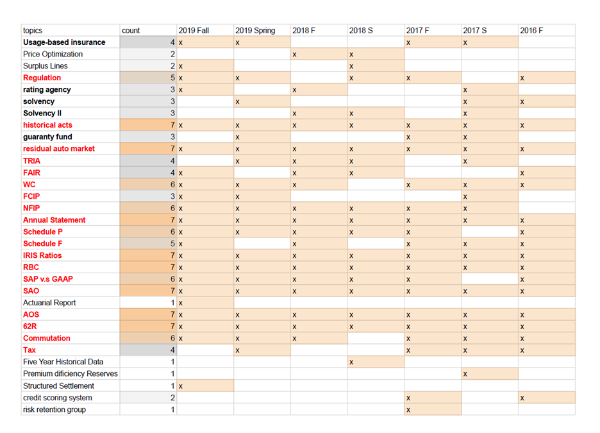

Thanks to my architecture design experience, where there is never enough time and things are never finished, I have grown comfortable with leaving certain things behind while prioritizing and delivering the most important things. Often, when design packages are delivered, the toilet and elevators are just boxes drawn on the plan. And that’s fine. Don’t spend all your time figuring out the toilets and elevators. Instead, spend extra time polishing the front of the house, crafting the lobby space, maneuvering and test fitting the most important space in order to spend your time (and your client’s money) wisely. The same goes for studying for the exam. SOA and IRIS ratios are topics on every exam. Study them thoroughly. Premium deficiency reserves and structured settlement have only been on the exam once in the last five years. Go through them but don’t sweat it and don’t let it become a roadblock. I have included a list of “always tested topics” and “seldom tested topics” at the end of this article.* (It’s possible that the exam committee will also read my article and change their question structure. Don’t worry. The core knowledge shouldn’t shift: my strategy is to prioritize what’s most important, which still applies even in the case of rare events.)

Timeline challenge: Order matters

In this case, my timeline dictates that I have six weeks to use. My strategy can be summed up as “Foundation - Tectonics – Cladding". I will explain them now. The source materials are my foundations. I allocated three weeks to go over all of them; previous exams are the tectonic – structure members. They will help me predict what is likely to be tested in the future exam. I allocated two weeks to do them. Review and summarize the works done will help me tie together all the effort I’ve done before, and to go over the standard answers will help me polish my wording. These are my cladding, and I will leave a week to do it right before the exam.

If I had more time, I would still keep the proportion of the time allocation: 50% of reading, 30% of practicing, and 20% of reviewing and memorizing.

In a less ideal situation when I have less time, I would sacrifice some reading time but keep the practicing and reviewing since the latter two don’t scale as much as the first one.

Program Challenge: It’s purely a numbers game.

The mission: There is x amount of knowledge I need to understand to hit y score and pass the exam. That x amount of knowledge is scattered somewhere among the z pages of study materials.

I created a spreadsheet to track down the z pages of study materials. Excluding the ones from the study kit, which I decided not to buy, there are about 45 items listed in the syllabus. I only had access to the ones that are free, which boils down to 34 of them, with a rough page count of 2,000. Given that I have three weeks to read through them, it means I must read about 100 pages per day. As I know myself to be a more sporadic than systematic human being, reading 100 pages per day is not a realistic goal. Instead, I plan to read 150 pages per day, and after two days I can take a day off. This is what I call the “create a system and then break it” strategy, a common tactic in architecture design. You see it in the window arrangements and balustrades on large civil buildings. There will usually be a row of identical columns, creating a rhythm, and then something irregular happens, like a door or a protruding window, which “breaks” the pattern but in a way makes the whole design more interesting and dynamic. In practice, it helps you to have an automated system that also allows space for flexibility and adaptability because life is full of surprises and interruptions.

As I started the readings, I realized that many papers are only partially required. I trimmed off the reading list and ended up with about 1,100 pages. That allowed me to lower my daily reading goal to 75 pages per day, with a few days off in between. I also kept track of my progress as if there were weekly project status check-ins. This helped me understand where I was in comparison to my projection and whether my strategy needed calibration.

The page counts of the exam content also shed light on the weights of each component in the exam. According to my estimation, section C weighs the most, requiring 858 pages of reading out of the 1,101 total pages, which counts for 78% of the whole exam. The whole distribution is shown below:

| Section A | Section B | Section C | Section D | |

| Number of articles | 9 | 4 | 17 | 5 |

| Page Count | 121 | 56 | 858 | 113 |

| Percentage | 11% | 5% | 78% | 10% |

Note that the total percentage adds up to 104%, which is a result of the NAIC Solvency Regulatory Framework that is in both sections A and C.

Emotional management: Focus on the master plan. Be kind to yourself.

From my previous architecture experience, I’ve learned that frustration and stress can happen in any project phase. The pressures of approaching deadlines and the regretful thoughts of “should have” and “shouldn’t have” are inevitable. But in retrospect, these feelings are seldom productive. These feelings are often distorted and don’t reflect my actual progress. Same applies to CAS exams: emotions are not productive for taking exams. I’ve seen many brilliant, aspiring actuaries get stuck with one exam (myself included) and overwhelmed by the fear of failure. It’s important to recognize that you’ve done more than you think and that the goal of taking the exam fits into a larger picture, which is the master plan of your life. You are taking the exam to improve the quality of your life, not to release havoc and jeopardize your inner peace. My solution: the hallucination method. I know that I will always be my best ally and biggest cheerleader, so I decided that instead of getting frustrated about my pace and the challenging content, I would set aside my emotions and simply chew through the text as if I wasn’t confused at all and keep moving forward. This tactic paid back—by the time I was 80% finished with every paper, the previous 20% that was confusing had become clear.

Part 3: Conclusion

Taking an exam is like many other challenges in life: daunting to think about, exhausting to go through, and frustrating when you don’t succeed. However, in the world of architecture, nine out of 10 projects will experience failure at some point of the progress, whether it’s the concept, the schematic, or during construction. And life carries on. Many successful architecture firms have equal numbers of finished projects and ongoing projects with no apparent end in sight. But the lessons learned from the unfinished ones are valuable. They teach you something about the limitations of your own strengths: financially, intellectually, physically, and of the market itself. Studying for exams is a similar experience; I learned the most from the exams that I had to study more for than the ones I passed swiftly. In the end, the exams are intended to help us navigate real-life situations that don’t always follow a syllabus.

Appendix:

List of frequently tested subjects: